One of our goals at Alberta Classical Academy is to educate the aesthetic emotions and sensibilities of young learners, orienting them towards the sublime and the beautiful. We accomplish that, in part, by providing pupils opportunities to encounter beautiful works of art on a daily basis through in-class instruction, as well as in the physical environment of the school. Each of our campuses has a curated collection of artwork from around the world, depicting paintings, frescos, statues, and architecture that inspire wonder and contemplation.

A partial list of artwork displayed in our schools is provided below.

Jacques-Louis David (1748 – 1825)

Oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Death of Socrates depicts the execution of the philosopher Socrates in 399 BC, as described in Plato’s Phaedo dialogue. Charged with impiety for introducing new gods and failing to honour the gods of the city, Socrates had been sentenced to die by drinking poison hemlock. In the painting, he is shown sitting upright on a bed, dressed in a white robe. One hand is extended over the cup of hemlock, and with the other hand he points to the heavens. While his friends are shown in emotional distress, Socrates meets his impending death with serenity, and expounds on the immortality of the soul. Plato is depicted at the foot of the bed looking into his lap, and Crito grips the knee of Socrates.

“Wherefore, O judges, be of good cheer about death, and know this of a truth: that no evil can happen to a good man, either in life or after death. He and his are not neglected by the gods.”

– The Apology

The Death of Socrates (1787)

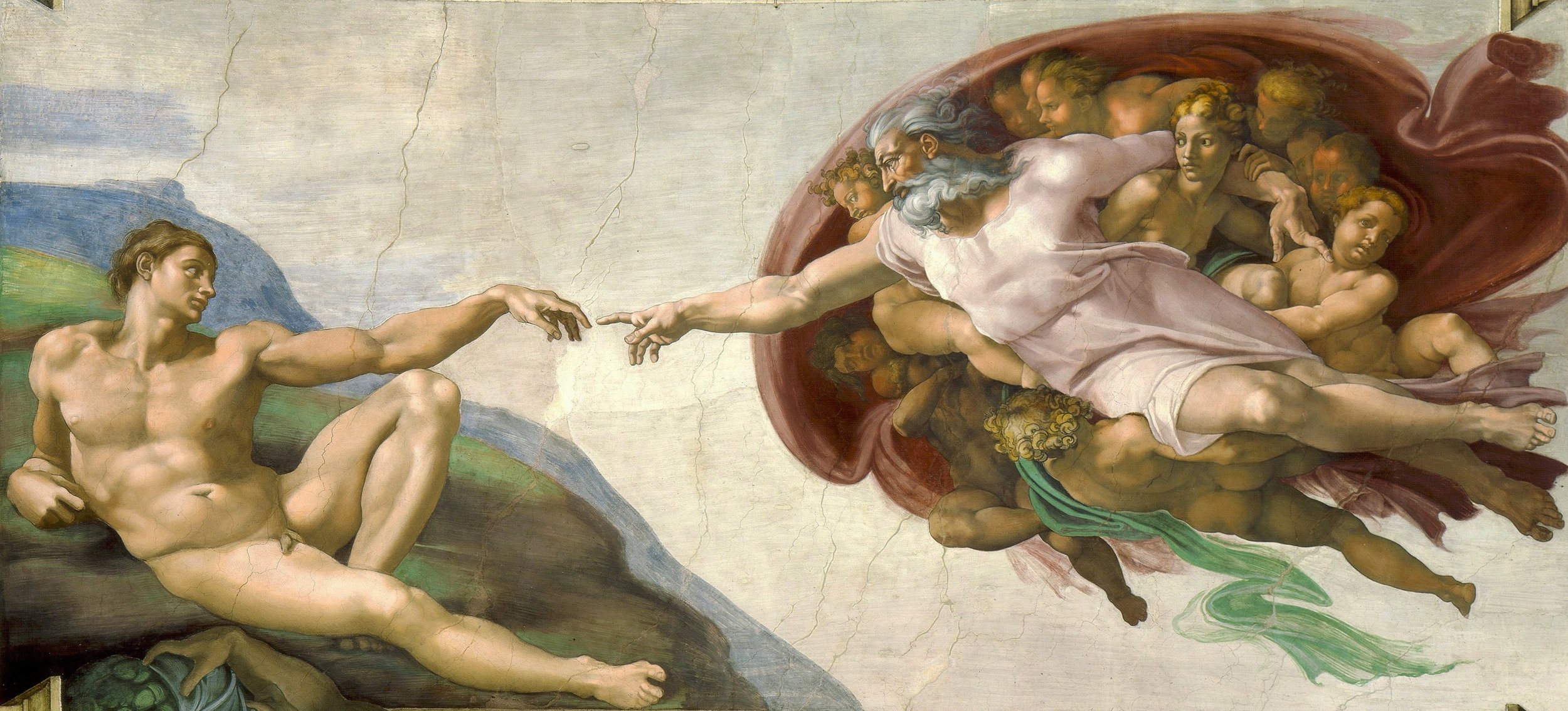

Michelangelo (1475 – 1564)

Fresco, Sistine Chapel, Rome

The most famous and widely reproduced panel from the Sistine Chapel ceiling fresco in Rome, The Creation of Adam depicts God’s creation of man as told in the Book of Genesis. God is shown on the right as an white-bearded man wrapped in a flowing cloak. He extends his right arm toward a naked Adam, on the lower left, who mirrors God’s gesture. God’s arm and finger are fully extended toward his creation, but Adam’s finger remains partially contracted. This seems to imply that God is there, but the decision to seek him belongs to us.

“ Then God said, ‘Let us make humans in our image, according to our likeness, and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over the cattle and over all the wild animals of the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.’”

– Genesis 1:26

The Creation of Adam (1512)

Giovanni Paolo Panini (1475 – 1564)

Oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris

Modern Rome (also called Picture Gallery with Views of Modern Rome) presents famous works of Renaissance art that adorned the city at the time of Panini’s painting. Among the monuments, sculptures, and buildings depicted are the Trevi Fountain, the Medici Lion, Michelangelo’s Moses, Saint Peter’s Basilica, the Cathedra Petri, and Bernini’s sculptures of David, Constantine, and Apollo and Daphne, among others. This was the third and final version of the painting by Panini. It is the companion piece to his painting Ancient Rome.

Modern Rome (1759)

Jacques-Louis David (1748 – 1825)

Oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris

In his history of Rome From the Founding of the City, Livy (Titus Livius) recounted a legend about a dispute between Rome and a rival city, Alba Longa, in the seventh century BC. To settle the dispute, each city agreed to choose three champions to participate in a ritual fight to the death. This painting shows the Horatii family, whose three sons (left) vow to lay down their lives for Rome. They are saluting their father (centre), who holds their swords. Representing the city of Alba Longa are the Curiatii brothers, all of whom were killed in the subsequent duel.

On the right side of the painting is Camilla. She is the sister of the Horatii brothers, but is betrothed to marry one of the Curatii. Joining her in her grief is Sabrina, a sister of the Curatii who is married to a Horatii. The painting celebrates the virtues of courage, loyalty, and sacrifice, while also highlighting the tension between public duty and private affection.

Oath of the Horatii (1784)

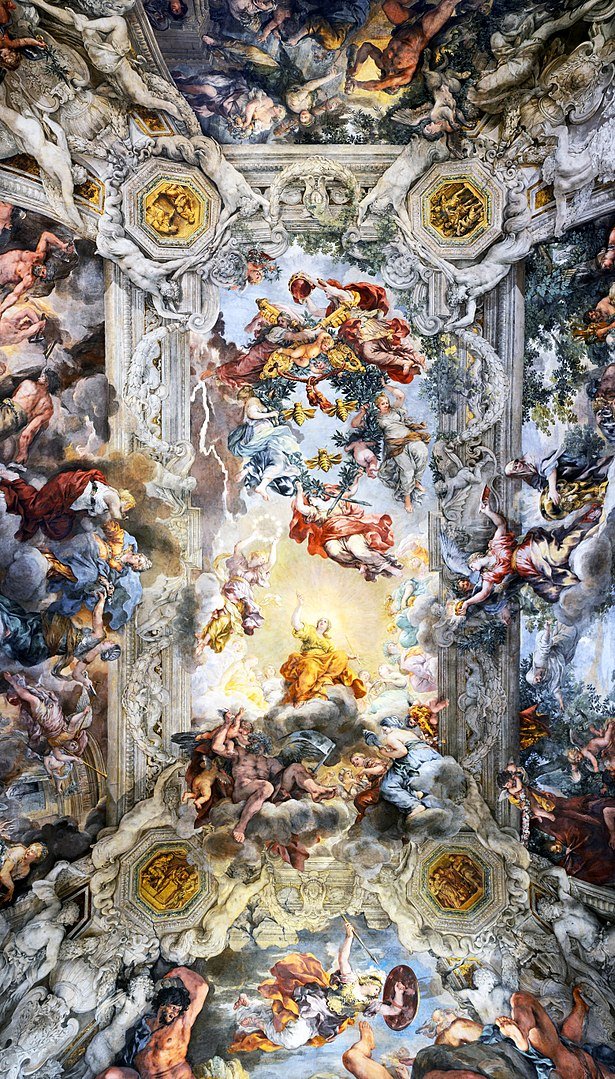

Pietro da Cortana (1596-1669)

Fresco, Palazzo Barberini, Rome

The Allegory of Divine Providence is one of the most iconic fresco paintings of the High Baroque era. It is a captivating example of optical illusion, a key feature of the Baroque style, which draws the viewer into the drama. The central figure is Divine Providence, who is depicted surrounded by light and about to receive the crown of immortality. On the opposite end there is another crown made of leaves that surround three bees, the iconic symbol of the Barberini family, which sponsored the fresco. The four octagonal medallions at the corner of the fresco depict the four cardinal virtues (prudence, justice, fortitude, temperance), and the animals below the medallions correspond to each virtue. Mythical figures are placed outside of the rectangular frame in the fresco. The location of these figures in the fresco signals the hierarchy of influence over human affairs.

Allegory of Divine Providence (1633)

Raphael (1483 – 1520)

Fresco, Apostolic Palace, Vatican City

The School of Athens is widely considered to be Raphael’s crowning masterpiece, and one of the best-known works of the Renaissance. Commissioned by Pope Julius II to decorate his library, the fresco depicts many of the leading philosophers of Greek antiquity. Standing at the centre of the painting are Plato (left) and his student Aristotle (left). Both men hold copies of their books — Plato is grasping the Timaeus, and Aristotle holds Nicomachean Ethics. With his right hand, Plato points to the heavens, while Aristotle’s right palm is facing down, his hand held parallel to the earth. These gestures contrast Plato’s interest in the eternal and immaterial forms with Aristotle’s focus on the particulars of this immanent, physical world.

Several other prominent philosophers are represented in the painting. Socrates is shown in an olive green robe to the left of his student, Plato. He appears to be in conversation with a military commander, thought to be either Alcibiades or Alexander the Great. Epicurus, wearing a crown of leaves, is shown writing. Pythagoras is in the lower left with a book, next to Archimedes who displays a theorem on a board. Foregrounded on the right are astronomers Ptolemy and Zoroaster, and who are holding terrestrial and celestial globes. Euclid is also near the right, using a compass to illustrate a geometric concept. Diogenes, dressed in a blue robe, is sprawled on the steps. In the background are found statues of Apollo—god of truth, poetry, and prophecy—and Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and justice.

The appearances of several figures in the paintings are based on Raphael’s friends and contemporaries; Plato, for instance, is painted to resemble Leonardo da Vinci. Heraclitus, who is shown writing on the steps, is modelled on Michelangelo. Raphael painted himself in the right-hand corner, wearing a black cap and gazing at the viewer.

The School of Athens (1511)

Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus

Marble, Vatican Museum

In the tenth year of the Trojan war, the Greeks devised an ingenious strategy to breach and destroy the impenetrable city of Troy. Greek soldiers concealed themselves inside a giant, hollow wooden horse. The horse was wheeled up to the city gates and presented as a peace offering to the Trojans. An emissary explained that the Greeks had surrendered, and were sailing back to their homes. The Trojan priest, Laocoön, warned his compatriots not to trust the gift, and hurled a spear into the flank of the wooden horse. The Goddess Hera (Juno) then summoned a sea serpent to devour Laocoön and his sons. The Trojans saw this as divine punishment, and welcomed the horse into their city. That night, the Greek soldiers crept from their hiding place inside the horse, opened the gates, and burned the city. This marked the end of the Trojan war, and the beginning of the epic stories the Odyssey and the Aeneid.

“Poor doomed fools, have you gone mad, you Trojans? You really believe the enemy’s sailed away? Or any gift of the Greeks is free of guile? Is that how well you know Ulysses? Trust me, either the Greeks are hiding, shut inside those beams, or the horse is a battle-engine geared to breach our walls, spy on our homes, come down on our city, overwhelm us— or some other deception’s lurking deep inside it. Trojans, never trust that horse. Whatever it is, I fear the Greeks, especially bearing gifts.”

– Laocoön warning the Trojans, as recounted in Virgil’s Aeneid